The 2023 Blue Note Jazz Festival: A Blueprint For A Better World

Dave Chappelle and Robert Glasper’s The Blue Note Jazz Festival is about something much bigger than its conceit. The festival, now in its second year, is generating a blueprint for collective attunement and providing an intentional space of beauty, joy, and camaraderie. It’s a place where Black and African diasporic cultural traditions can be transmitted and transformed. As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of hip-hop this month, we turn to epic intergenerational hangs like this one — which went down at the Silverado Resort in Napa Valley, California last weekend — to take an honest pulse of the culture.

From witnessing Bilal scatting with Lalah Hathaway and Philip Bailey to the continuum of the McFerrin family (Bobby, Taylor and Madison) improvising on stage to Rakim freestyling in the same extemporaneous cipher as Talib Kweli and Chance the Rapper, this year’s festival felt like a rip in the fabric of spacetime opened up just to receive the boundless divine sounds bursting forth from Napa Valley.

We had the privilege of breaking bread with a few of the torchbearers of Black music and culture — from comedy to folkloric African diasporic tradition — to talk about a wide spectrum of topics, from the fraught history of jazz as a category to the responsibility of the artist to reflect the times, to what the next 50 years of hip-hop will bring. Through connecting with this continuum of living legends, we have the unique opportunity to learn from, metabolize and integrate the hard-earned wisdom of Digable Planets, Robert Glasper, Nicholas Payton, Meshell Ndegeocello, Weedie Braimah, Affion Crockett, and Amir Sulaiman.

Each of the following conversations were recorded separately with each artist and composed in the edit as a collective conversation for stylistic purposes.

ISA: We’re here at the Blue Note Jazz Festival in Napa Valley for the second consecutive year and musicians throughout history from Sidney Bechet to Duke Ellington to Anthony Braxton have explicitly refuted the label “jazz” as an adequate descriptor of their creativity. In an interview with music historian Graham Lock in his book Blutopia, American composer Anthony Braxton decried “jazz journalism can be reduced to attempts to make reality out of a process that has to do with becoming.”

What’s your relationship to the category of jazz and to the act of labeling your art period?

Nicholas Payton: Well, I think you already know that I'm not a fan of the word. I find it to be oppressive. I think it's the musical equivalent of the N-word. To me, it puts you in a box. It means less album sales, it means less ticket sales. It means if you're a jazz artist and you win Artist of the Year at the Grammys, you don't get to play with your own band. Black music is the foundation of American popular music, period. Louis Armstrong was the world's first pop star. So the fact that you want to call this music “jazz” and sort of sit in the corner as this underground sort of thing where it's glorified to not make as much money or to be as celebrated, it's ghettoism. And I didn't get into this business to be second best or to be put in a corner.

Meshell Ndegeocello: I'm a student of Black American music so I believe it is something unique to growing up here and having a certain experience as a person of color, as people who were enslaved. I think there's a beauty and a depth to all music that comes from that diaspora. And I don't need a label because I play music for people who are seeking well-being or seeking a way to be more thoughtful, something to soothe their mind or lift their spirits. Yeah, I'm trying to have that eternal becoming. Well, he's [Anthony Braxton] along the lines of Octavia Butler. God is change and death adds shape to life. And I don't mean like the grand adventure of death but we die a little bit every day. If you think you're the same person you were a few hours ago, you're not. And so I'm just trying to grow gracefully, move through space and time without doing too much destruction and just have a good journey.

Weedie Braimah: Well, for me, first of all, we talk about me as being a folklorist, right? Folklorist and folkloric African and diasporic music. You can never take the people from its emotion, right? So a lot of times when people say “jazz” they really don't know the history behind it. So It becomes its own entity of what was created and not why it was created, under the circumstances how it was created, and where it went to where it is today. Black American music or for me, folkloric, Indigenous American, African centered music from African Americans or Africans born in America. No matter what you would say, it still has this emotional construct here. And with that being said, that's why for me bringing this music here, I even go through the same thing, because for me, when people see me, they say, “he’s a percussionist playing jazz.” When you messed up. Now we've already created a narrative with a vernacular. It has nothing to do with who I am and how I identify. And we're in the year 2023, in this era where we have to use terms that show how we identify. So because I play an instrument in a genre of music that doesn't identify what I do, I've created this new narrative. That's what “The Hands of Time” is. It's taking these older songs that were created off of the emotions and the sounds and the understanding and the spiritual aspect of a music that was created right here in this country but with a traditional folkloric foundation from West Africa and throughout the diaspora. So when you see and you hear bands like “The Hands of Time”, you start to realize that this is not what you would call jazz. This is djembe music because I always tell people, I play an instrument that has a name. I identify as being a djembefola on the djembe, and the word djembefola basically means djembe player. But why am I saying all this? There's no way that you can use a European vernacular to define an African narrative.

Robert Glasper: Yeah, I mean, it's an uphill battle. I just want to make good music. I don't really care what you call it because it's not going to sell more no matter what you call it. It only sells if it works and it sounds good and it feels good. And if it does something for your life. So whatever you call it, I really could care less. Obviously, the word jazz has some dark meaning from the past, but we as Black people have a tendency to take things that were bad and turn it around so it loses its power. That's one of those things. I love that.

Craig "Doodlebug" Irving: I think that people need labels sometimes to understand things. As an artist, as a musician, when you're making music, you ain't saying, “I'm making some jazz music” you're just making music. And when it gets to the place where they have to market it and start making money and it becomes a part of that machine, then they have to label it.

Ishmael "Butterfly" Butler: The people that do it and are really into music, they don't really feel like categories are necessary and often don't respect them. And I understand that because no matter if you hear a song that was from 40 years ago or or ten weeks ago, the way you feel about it is really something that isn't attached to any time. It's always in the present and leading you into the next second. it's just a way to code something because some people identify with those codes and gravitate towards them.

Amir Sulaiman: I think about it a lot because as a poet I consider myself part of a literary tradition, but I'm also a product of hip-hop. And so, like what I do — is it hip-hop? What makes what I do different from what, say, Rakim does? But it is different. Like we understand, even people that are part of the culture can make a distinction.

So I actually don't have a good answer for that because it's something I go back and forth on myself. I think, for example, poetry has something very unique to offer in the context of just culture, hip-hop culture and the culture wider than that. But also to say that rap isn't poetry is also kind of not true either. Labels can be expansive in that way but then also we know that labeling can be constricting and suffocating in a way so people feel trapped in a particular “genre.”

ISA: Since Blue Note Jazz Festival is hosted by Dave Chappelle and Robert Glasper, I’m curious to hear your perspective on the somewhat elusive and persistent love affair between the musician and the comic throughout history.

What forces are at play in the seductive dance between the two?

Meshell Ndegeocello: Pain and sorrow. And then let's head on back to Black American music. The experience of being a person of color in America is very specific. And I think the comedian does it with storytelling and levity and wit, and the musician does it with sound intimacy, melody, and rhythm to soothe you.

Robert Glasper: Everybody's always told me that they feel like I'm a comedian. And, you know, a lot of musicians try to be comedians. A lot of comedians want to be musicians in certain ways. But throughout history that's been happening. Musicians go on tour and have comics open up for them. So it’s not something that's uncommon — at least back in the day. I think now it's rare but yeah, it's great. I remember when I was playing piano with Maxwell when we were on tour and Guy Torry was on tour with us opening up the shows. It's always good to have a laugh.

Affion Crockett: Everything comes from a rhythm and a timing and a beat and comedy, music, swimming — whatever you name it. Everything is about timing. So that's the common denominator in everything, even in communication. You and I are talking right now. You say something, I give the beat, and then I respond. If we're clashing, now we're arguing or there's not a lot of coherence going on unless we're in harmony. Like when two singers are singing together and the notes are correct and in conjunction with each other. But in that same example, when the singers are singing and one of them is off, you can hear that. So it's timing, its rhythm, its key pitch, everything. All those elements blend comedy and music pretty well for me anyway.

Dave has always been a supporter of what I call real music. That's if you watch The Chappelle Show, he had De La Soul, he had Talib and Yasiin Bey, he had Ludacris. He had a lot of people that he just really enjoyed. He had early Kanye and Common on there, so many artists that were creative and real prolific. He let them have the freedom to design their own performances. So he's been a music fan and then with Block Party, the movie that he did years ago. Dave is just a fan of music because again, the same way I am, I'm not just a comedian. I'm a music head, too. I think it says a lot about Dave looking at Robert saying, “man, I'm a fan of yours and I want to help elevate your platform even more.” So, you know, to have two successful black men come together and support each other, there's nothing better than that. You know, it's too much competition out there or the illusion of competition that we feel like we got to hate on somebody else but now I love that they come together, show that unity and bring everybody out.

Nicholas Payton: Timing is a big part of it. It also gives us a glimpse to be out of our bodies and to reconnect to who we are outside of this physical form. When we look at shows back in the day, you know, Richard Pryor used to open for Miles Davis. That's how all this started so it's good to see that coming back.

ISA: In the opening track of Black Radio III, Amir Sulaiman has a powerful line that says, “We don’t play music / we pray music.” I so often feel that music is reduced to mere entertainment when it’s stealthily transmitting our non-renewable resources including our sacred secrets, generational wisdom and spiritual instructions for liberation.

What does that line “we pray music” mean to you? What does this music mean beyond the stage?

Amir Sulaiman: When I wrote that line I wanted to make a distinction about what we're attempting here, what our intention is here, that we're not just playing music. This isn't just for mindless consumption and doesn't come from a tradition of that but that this comes from a tradition of people transforming themselves and healing themselves and healing others and loving others by way of this freeing and liberating themselves by way of music and carrying themselves through impossible times and impossible circumstances by way of this music. So when we say “play”, it doesn't really hold the meaning that I wanted to relay. This isn't really playing, you know, this is praying. This is a communion that we're seeking with the divine reality and something that we're seeking with love and meaning from the essence of our being. And so this is different from just a pop hit or something that will go viral on Instagram. We're looking to do something real and more universal and eternal than that. And so that phrasing came to me and I was like, “oh, yeah, this is what I mean. This is what we're doing.”

Robert Glasper: Totally. That's the truth. Music is prayer to a lot of people. You know, it's the universal prayer. Music is meditation. It’s so important. It's a blessing to have the talent that I have to write music to share it with people and to throw something like this festival and to have all these amazing artists come here and pour their heart and soul out on stage and see how it helps and heals and and just makes so many people happy, you know, takes you out of the troubles you got going on. And whatever it is, it gives you inspiration, you know what I mean? Music does so many things.

Weedie Braimah: I'm playing for people. I'm playing for energy. I'm playing for you to heal. I'm playing for the emotion of goodwill. I'm not just playing because I like to play. Because if you realize the history of the music and the craft, you know it doesn't happen like that. You know that when you're playing for somebody, you're not just playing for them to be like, “oh, give me money” or “I'm about to play so people can go crazy”. I'm playing for goodwill, for peace, for health, for prosperity, for longevity. And if I don't do that, then the job of a djembefola is not being done. That's why you can't focus on the stage when you're dealing with culture because it's not a stage. What you're seeing is not for the stage. What you're seeing is in real time, you're connected to it, I'm connected to you to bring you into it. So when you leave here, you're healed and you're healthier than you were before you came. Now, if you listen to music here and if I don't cool you down, then I'm creating more harm for you than you really know as a musician. The musician's job is to take you somewhere but bring you back.

ISA: As a writer, I feel I carry a profound responsibility to use any airtime I get to be precise in my language and to say the things that aren’t being said to keep the culture in a more honest relationship with itself. In your opinion, what is the responsibility of the artist?

Amir Sulaiman: We can look at the economists that tell us how the economy is doing or we can hear from the politicians about the state of affairs of our nation but the one who is going to tell us how our hearts are doing is the poet. And so the poet has to witness the human experience and then be able to metabolize it into language and then relay it back to the ones that they are witnessing to give them the sense of satisfaction that comes with an accurate articulation of our state of being.

Affion Crockett: I think everything that is spoken is manifested. Everything that is seen is remembered. So we have to be mindful and that is across the board. We all have a responsibility from news anchors, movie directors, actors, rappers, athletes. We all have a responsibility to humanity to just be better. To just be kind. To just love. Accountability is not a popular thing because it forces you to look at yourself, all parts of yourself, not just the parts where you wake up and comb your hair and you got the fly cut and the lineup or the makeup is on or whatever you do. I look at myself as a mirror to society, which was my first standup special, and I'm holding up the mirror to society and myself.

Craig "Doodlebug" Irving: We all have a responsibility for ourselves, what we do in our life. I can't speak for nobody else, but if we all do our part, the combination is going to be a good thing. [There’s] always going to be all different types of angles to this music because everybody doesn't see the world the way you see it. And we just got to accept the fact that that's how it is. I just do what I can, teach my kids the best I can. Hopefully, they'll absorb it and take it on and take those jewels with them to the next generation. They're not going to take it all because you got to learn things on your own. A lot of things you got to learn on your own. But I try to give them enough space to figure out who they are. And that's what you got to do with hip-hop, let these kids figure out who they are. But at the same time, the OGs got to teach them. Like a lot of these young boys out here in the streets being led by cats who still don't know who they are. They lost. They grew up in a prison culture… so they don't know who they are.

Mariana “Ladybug Mecca” Vieira: I feel like every generation has their movement. People are either in tune to what they're in tune to or attuned to what they're attuned to. We are all responsible for the information that we know and whether we pass it along or not. It's up to you. Real change doesn't require 50% of the population to happen. Any real change in the past has been cadres of smaller movements all throughout the country that created the change that we have today and the fight is ever present. We can't get comfortable and be relaxed, we have to keep fighting and not feel like our back is against the wall. We can't create real change if we can’t even create change in our very own initial communities with our neighbors and our loved ones that are close to us. But we're pushing the energy forward, even though it may not feel like it.

ISA: I’m thinking of two Duke Ellington quotes about freedom. The first is, “If jazz means anything, it is freedom of expression” and the related second is “jazz simply means the freedom to have many forms,” which begs the question, what is the relationship between freedom and structure in the music? Between mastering “many forms” so that you can break or stretch them? I’m also curious about the relationship between discipline and improvisation.

Nicholas Payton: It's not either or, it's both. You can't have freedom without form, and there's no form without freedom. Ornette Coleman, who is kind of the vanguard of the avant-gardist movement, well, that came out of a response to the structure and the weightiness and almost the hyperstructure of jazz. That was his way of liberating it, which to me is why he called it free jazz. I look at that like it's freeing jazz. It's putting so-called jazz back to its primal roots. I don't think you have improvisation without form. The problem is that when we look at a lot of Black artists, we look at them as improvisers and it's almost like a sleight to say they don't know what they're doing or they're just making that up like years of craftsmanship and study doesn't go into that. What is called improvisation is really composition. It's just in real-time as opposed to when you're composing something, you're writing and you can take six months to write a piece or Stevie Wonder can take two years to write “Songs in the Key of Life” as opposed to when you see someone on stage, they're playing a solo. But that's really composition. It's just in real-time at that moment. It's sped-up composition. Improvisation is somewhat of a misnomer because it allows people to kind of discard the level of work that goes into it.

I have a quote from a book that I'm working on called Notes from the Zen Gangster. It's a book I've been working on for the last 15 years full of quotes and aphorisms and kind of like a thought of the day. But I have one quote which says, “A mistake is the truth trying to come out.” So the whole premise is that it's through discipline and through the work that you earn the right to make a healthy mistake, an informed mistake. But you can't bypass the years of study. And you're not going to grab someone out of the audience and give them the horn and say, “OK, you make a mistake.”

Robert Glasper: You’ve got to have some discipline and learn. Sometimes as a musician, you can sit down and play for hours and say you're practicing. And a lot of musicians do that. I, myself included, was guilty of that until I learned how to practice. You know what the distinction is when you just play for hours, you're just playing stuff but you didn't get up to learning something new. You're getting good at playing what you already knew versus playing something that is harder that you've not mastered yet and learning it slowly. And when you get up from your instrument or whatever you do, you can actually do that better than you could when you first sat down. So it's trying to get through some harder things versus just playing what you already know.

Affion Crockett: The real message and my interpretation of what Bruce Lee’s “be water” means is be free. Be free to create from your spirit versus some structure because when you create freely, it doesn't matter what structure you are in, you can still be yourself within that structure. That's what “be water” means. If it's in a cup, it becomes the cup, if it's in a kettle, it becomes the kettle. But the water itself, the element of water, the substance of water is free, like the spirit, like freestyle creativity. It's free. Of course there's structure and there's notes and music theory and all that kind of stuff to be learned. And all these musicians, we know they know it, right? Robert Glasper, Terrace Martin, Keyon Harrold, all of these guys, they all know it, but within knowing the structure, they can freestyle.

ISA: Before we get into the meaning of the 50th anniversary of hip hop, I want to ask about your personal evolution as people. To me, music and life are symbiotically related so as we transform and change so does the music. I think this country is too obsessed with nostalgia and freeze-framing artists in a glamorized past that they refuse to complicate or update but it’s essential to give musicians space to evolve and grow.

How would you describe the present moment in your journey?

Mariana “Ladybug Mecca” Vieira: I was a young mother of three. And so now that they are grown young men, I've entered into an entirely new chapter of my life. I moved to Los Angeles. I'm building a really beautiful, creative community of people where I'm getting to experiment and just dig deep within myself creatively, spiritually and personally and that allows for that. It affects every part of my life. And I'm excited about it.

Craig "Doodlebug" Irving: I was in my early 20s when I was making music, I was in a whole different mind state. I was trying to travel the world. Have fun and party. “Where's the girls at? Where the weed at?” I've gotten to a point in my life where I have a family now. I'm married so now I have a more stable life. I’m still on the political thing and I still want to have fun but in a more structured way. Now it’s more about the kids. It's more about the next generation. Back then it was about competition and showing how fly we was and how cool I could rap. I don't really care about that no more. It's about the community, the culture and progressing as me personally as a man.

Ishmael "Butterfly" Butler: I feel good because something I discovered is the key to energy and a bright outlook is to learn something new. So I try to learn new stuff, new equipment, new instruments and a new approach, and then practice it and then do it when you're just not practicing either. So that's cool. Just like trying to do something new. And we get lucky because we get to perform a lot too. So it's always exciting to perform.

Meshell Ndegeocello: I've watched a lot of people in this business fall prey to things. So I think right now, I get to be around my friends, I get to be with my family and eat good food and meet beautiful people and talk. I keep it real simple. That's what I've learned. Keep it real simple.

ISA: From where you sit, is hip hop in good hands? What significance does this 50 year marker carry for you?

Robert Glasper: Hip-hop is the youngest popular music and yet it’s so influential. It's the biggest music right now on earth and I'm a child of hip-hop. It’s music that was born from struggle. And it's music that is based around freedom and fighting against the powers that be. It was the voice of Black people, the voice of people living in poverty and all kinds of things that just represent us as people of color. And to see that music go so global that now everybody wants a piece of it, everybody wants to be a part of it. It's amazing. And it's great that a lot of the people are still around that pioneered this music. That's why it's so great that Rakim is here and Digable Planets is here and De La Soul. So many of our people who are the architects of this are still here so we’ve got to give them some flowers while they're living.

Affion Crockett: I feel like hip-hop is like its age. A 50-year-old begins to thin in the hair. Body deteriorates a little bit. Mind starts to go. I think as much as the popular answer is to say “hip-hop is in great hands and the future is now” I don't believe that. I believe there's not enough accountability. There's too many murders. There's too many people talking about drugs and stripper poles. And that's the leading sound and the leading narrative that we're hearing. In my personal opinion, I feel like hip-hop may be getting old and thinning out as much as they try to reinvent it or bring new artists out there. New artists are great. There are some that are great and there are some that are not but if we don't get a hold of those sounds and those speakers and those words that are coming out of them, I don't know where it's going to be in 50 years.

Craig "Doodlebug" Irving: I do think hip-hop is in good hands. The music is definitely progressing and it's going in a different way. If you look at the world of hip-hop in mainstream terms, maybe not, but if you look beyond that, you see Coast Contra, Sa-Roc, Rapsody. There's just so much out there that's keeping the culture and the foundation strong so you gotta just let people be who they are. That's what makes the world go round is the diversity. You got to have some wild cats talking about something crazy and some people want that conscious. They want it when they hear the lyrics. They want you to be able to take them somewhere and make them forget their life. As long as we got all that, we’re good. I mean, I don't like everything that's out now, but I didn't like everything that was out back in the days either.

Ishmael "Butterfly" Butler: Yeah, it’s tough out here now. Rap has always kind of been like an opposition, a counterculture. And it's not doing that much no more. And to be that far away from the sentiment of your origin is… it means that it’s sick. So I think it's a desperate time right now creatively, but also culturally and environmentally and all that. The closing in of everything makes people feel desperate and scared. And so the music isn't really that loving.

ISA: What is your prayer for the next 10 years of hip-hop?

Craig "Doodlebug" Irving: My hope for hip-hop is to just continue to build on the creativity that we started in the early ‘80s and just go wild. Be as creative as you can be. Don't let the naysayers hold you down and keep your creativity from reaching its boiling point. I'm hoping that the young boys and the young girls just go out there and just create without worrying about, “Oh, is this hitting? Is this what everybody is trying to listen to?” Don't worry about that. Just do what you do and the people that's supposed to resonate with it will resonate towards it.

Ishmael "Butterfly" Butler: In the next 50 years, I hope hip-hop breaks the world and reshapes it again in a cool way and a jiggy way like it did the time before.

Robert Glasper: My prayer for the next 50 years of hip-hop is that it keeps evolving. We're not supposed to like everything that evolves. You don't have to like it if it goes somewhere you don't like — that's kind of the history of everything. The history of music, the history of everything. One generation does something, the next generation does something. And the older generation says, “Wait a minute, that's not blah, blah, blah, blah.” And then the younger one goes, “yes, it is!” And then you keep it moving. You need that. So I just pray that it keeps moving. I’d rather something keep moving and go somewhere I don't like than it just stays still and stays stagnant because that means there's no more creativity.

Affion Crockett: I hope that hip-hop gets better, to be a little more balanced. A lot more balanced, actually, with the types of artists that we allow to break through and that we choose to support. I hope that we can choose to support just a few more artists that are really saying something and who have some real humanity in their lyrics.

Weedie Braimah (djembefola): The music that you're hearing now, it has evolved. We're representing the 50-year anniversary of hip-hop. Now, look how even this hip-hop music was created and why people like Idris Muhammad, John “Jabo” Starks, Clyde Stubblefield, Olatunji, all these legendary drummers were sampled by J Dilla and all these people. My uncle, Idris Muhammad, would talk about that a lot. But the question is, “What are they going to do with it?” I remember he said that a long time ago. And so he was like, “If it's alive, it will stay alive forever.” Because when people pass away, they don't pass away just to transition, to go in the ground. They transition so that their music and their thoughts and their actions live forever. That's music. So when we're talking about this word jazz, you start to realize that there's something bigger than the word that's going to be here forever and a day, and that forever and a day is being represented right here in this festival this weekend. So between the 50-year anniversary of hip-hop, between all the musicians that's here, that's playing these different genres that are creating this relationship and this new narrative in the year 2023, it shows that the music has evolved and so has the emotion and so has the spirit of the music. We look like we’re just playing some stuff but we're getting deep.

Amir Sulaiman: Fifty years? That we develop better language to talk about and spread and magnify love. Hip-hop in the early part, we had a lot of party music and then we had a lot of the descriptions of the challenges that we were facing in our environment in the inner cities and whatnot. And now we're in another place. But I would hope that we can use the craft to better talk about love. And when I say love, I don't mean that all of them have to be love poems or love songs or romantic music. Hip-hop has that in its origin so it's not something new I'm talking about introducing, but that it becomes a mechanism that we can relay and spread love more deeply and profoundly among each other.

Originally published on Okayplayer on August 3, 2023

This Is Not Noise: Inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival Makes History

“[Both] of them, the spirituals and the blues, they was a prayer. One was praying to God and the other was praying to what’s human. It’s like one was saying ‘Oh God, let me go,’ and the other was saying, ‘Oh Mister, let me be.’ And they were both the same thing in a way; they were both my people’s way of praying to be themselves, they had a kind of trance to them, a kind of forgetting. It was like a man closing his eyes so he can see a light inside him. That light, it’s far off and you’ve got to wait to see it. But it’s there. It’s waiting. The spirituals, they’re a way of seeing that light. It’s far off music; it’s a going away, but it’s a going away that takes you with it. And the blues, they’ve got that sob inside, that awful lonesome feeling. It’s got so much remembering inside it, so many bad things to remember, so many losses.” - Sidney Bechet, Treat It Gentle

“We don’t play music, we pray music.” - Amir Sulaiman, “In Tune”

Photograph of Blue Note Jazz Festival crowd (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

It’s easy to overlook the obvious but sometimes the truth is hiding in plain sight. As recognizable as Blue Note is worldwide, not many people know what a blue note is in the context of the music itself. Without getting lost in the weeds of music theory, academic Lindsey Valich defines blue notes as, “notes ‘between the cracks’ of conventional pitches''. Foundational to both blues and jazz, blue notes stretch outside of the scale for expressive effect - they subvert expectations in pursuit of an honest sound. And this search, this insistence upon authenticity, is one of the connective threads of the artists who made history this weekend in Napa Valley at the inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival.

Photograph of Blue Note Jazz Festival crowd (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

Let’s be clear that all festivals, even the ones with the line-up of a lifetime, run on a certain formula to maximize profit. A bottle of water will run you $8, VIP tickets will cost double even if the difference between the two tiers is minimal. Festivals are their own microcosms for America, fraught with the same power struggles, hierarchies and long, inefficient lines for food. I’m not interested in justifying the inaccessible price points or painting a glamorous picture of a much more nuanced reality. I am however interested in the music and the brilliant and complicated people who make it.

Photograph of Thundercat (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

Photograph of Thundercat (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

While at the Blue Note Jazz Festival this past weekend, we sat down with three standout artists on the bill: Jahi Sundance, Alex Isley, and Amber Navran to catch up, learn about their relationship to jazz, and get a sense of their first-hand experiences performing and attending the festival.

JAHI SUNDANCE

Multi-instrumentalist, producer, and DJ Jahi Sundance and I sat for an interview on a green sofa in the press lounge, finding momentary refuge from the insufferable afternoon Napa heat. As the son of Oliver Lake, a renowned jazz saxophonist, flutist, composer, poet, and visual artist, Jahi comes from a lineage of jazz that has informed and shaped his unique approach to DJing.

To borrow a phrase coined by historian Mircea Eliade, Jahi acts as a “technician of the sacred” throughout Robert Glasper’s evening sets and each night the circumference of his vibrational cipher holds within it the heaviest players alive from Kamasi Washington to Thundercat.

Photography of Jahi Sundance (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

What was your relationship to jazz growing up? When did you get introduced to it and since you come from a musical family, were you drawn to the music off top or did it take time? Last question in this Russian Doll of questions (ha), what's your current relationship to both listening to jazz and its influence on how you DJ?

JAHI: My dad's a jazz musician. His name is Oliver Lake. He's a saxophone player. He's recognized in many ways in the jazz world. So when I was born and came home from the hospital, Dad was having rehearsal and they wrote a song for me. Jazz is my whole life, there’s no escaping it. I was a backstage baby as a kid growing up backstage at jazz shows with jazz people doing jazz stuff with jazz cats my whole life. It was never music that I didn't like because I didn't have a choice not to like it because I grew up listening to it. You may act like you don't like it when you're a teen but you like that shit. You know what I mean? It’s all you know. I played saxophone all through middle school and high school and college in jazz groups and did a bunch of jazz shit, jazz camps, all the jazz stuff you can do. And so, I'm in jazz, you know what I mean? Linking up with Robert [Glasper] and Christian McBride, with all those people, has been just a natural process of my life.

JAHI: So, you know, being at this Blue Note Jazz Festival and being able to perform at Blue Note in New York with Rob and Blue Note in China has been amazing. And part of that legacy is being able to bring a different approach to DJing. An approach that's really inspired by jazz. That's inspired by fitting into the music in an improvisational way that's not predictable and is more emotionally responsive to the music that's happening in the moment, within the confines of the tune, but still expressive and not necessarily just executing parts. There's a lane that I've carved out that has to do with a level of musicianship that is inspired by jazz. And as a result, the musicians that I play with have allowed me to do that on their records.

Photograph of Jahi Sundance (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

JAHI: What I'm really trying to do with DJing is be like a record, be like a circle around the entire band. So I'm trying to affect and respond to everybody's playing in the entire band in subtle ways, not all at once, but still encircling the whole band. I’m trying to be a circle around everybody, no matter which shape they may be in, whether they're a triangle or square or a circle themselves. I'm always trying to be a circle.

Photograph of Jahi Sundance (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

We’re at the Blue Note Jazz Festival and one interesting thing I’ve observed is that not a lot of people know what blue notes are in the context of the music. For those who don’t know, can you define it for us?

JAHI: Blue notes are the notes that are outside of the scale, generally. Every song has chord changes and those chord changes determine the scales that you can play in. And then there are notes that are outside of the scale. But the truth is that a lot of times, when you stretch to those notes outside of the scale, that's what created a lot of different versions of jazz, was people rewriting what could be played inside of the scale.

That was a beautiful answer. Thank you, Jahi. I asked the question because I think blue notes as notes outside of the scale is an apt metaphor for the music you make - the way it cross-pollinates genre, style and approach. You are not someone who is beholden to convention but someone who stretches and straddles multiple emotional registers and musical traditions. I’m curious how you would self-describe where you sit musically?

JAHI: I feel like more important than genre, more even important than even your own self-labeling that you may want to do is authenticity. That's the barometer for all of my choices. Like every single choice that I make is based on what I think is authentic or not. There's literally no genre that is out of bounds because there's authenticity inside of all forms of music. And if you can find it and touch it, then you should be able to relate to it or at least I can.

I’m going to ask you to define authenticity only because I feel like that word means different things to different people.

JAHI: I feel like people have weird rules for art. And part of it is because art goes through phases and it's created and then at a certain point it's institutionalized and then it starts to be taught. And those phases of art we can see with hip hop, right? Hip hop just started in the late seventies and it's been institutionalized recently over the past, I'd say, 15 years. You see universities popping up with hip hop departments. Cornell has a collection and Harvard has a collection, and now they're buying stuff. They're going to the old hip hop guys and saying, ‘you know, let me buy all your chains and your paperwork and all your old stuff and all your collections of records’. And so those collections are now becoming valuable. And now we're seeing hip hop being taught. You can go to a class to learn hip hop. And so these phases of art sometimes get us into an idea of what's authentic by programming us to say the authentic jazz is John Coltrane of this era or Miles before the electric band. Authenticity is not a teachable thing. This [music] is a gift I have from my mom, who is able to tell when things are authentic or not just through existing. It's not about what somebody is going to say or what some rules are going to tell you. Authenticity is literally something that we're always looking for.

That was a really beautiful answer. There’s so much spinning in my head after what you said. I spend a lot of time thinking about the critical difference between preserving culture and institutionalizing it. I think someone like Greg Tate was an example of a music historian who acted as a witness rather than a voyeur. I feel his loss in this moment where music journalism consists mostly of tower of babel twitter commentary largely produced from an outsider’s perspective. Can you elaborate on the part institutions play in commodifying the music?

JAHI: First of all, speaking on Greg Tate, I had known Greg for about 20 years. Amazing person. He was writing about my dad and writing about my brother and writing about Michelle and writing about all these people who are close in my life. I met him just being in New York, going to Joe's Pub and, you know, you meet Greg Tate hanging out. He was a man beyond reproach. What a beautiful voice that we lost.

JAHI: When it comes to institutions, I don't have any problems with them teaching jazz - the issue is more about when that starts to become the definition of what's possible. What happens is you have these institutions like “Jazz at Lincoln Center” and others where they are offering a program that doesn't include anything that's far to the left. And that really doesn't shine a light on the entire breadth of what happened with jazz and particularly what happened with the heroes. What happened with Miles, what happened with Coltrane, what happened with the people that we really laud is that towards the end of their careers, they were searching for something more. They were searching for a way to speak to God on their instrument. And that brings you past all the possible things you could learn in an institution or all the possible things you could do when you have a strict definition of what's possible inside of the music.

You spend your whole life learning something to only get to a point to say, shit, I have to forget all of it. If you want to get to the next level, you have to forget everything that you learned going there. But all those things going there were all the things that you needed. So it's alright. But that's the real shit. Look at all the emcees who are relevant for over 20 years. It's a very small club. Most of them had to forget how they rapped before at a certain point to stay relevant. You have to forget. You have to come up with something new to do. You really do.

Oof, yes! You have to subvert your own convention. Sun Ra comes to mind as an embodiment of an artist who was searching for something more - something beyond the gaze or validation or false comfort of an institution. He had the audacity to create his own myth, which emerged from and braided together many existing traditions, and insisted upon it. He didn’t ask for permission, he made a decision and invited artists to join him in it. We have the power to create pathways of production and distribution that don’t depend on the obvious. Though, I suppose, It also doesn’t have to be mutually exclusive but the Lincoln Center certainly isn’t the only avenue for visibility and reach - especially not for real impact. I’m curious how you have navigated the different pathways available to you? Where do you find encouragement when you want to take a risk?

JAHI: I used to DJ, just like most of my DJ friends, in clubs every night in New York and I always give a shout out every interview to Michelle Ndegeocello, who took me on tour and gave me a space on stage to experiment and start DJing in a different way. That space allowed me to develop a style that is unique to me and that requires a lot of like saying no. When I moved to L.A., I met some drug dealer rappers who were coming to a club I was DJing at, and they had mad cash and they were like, “we want to do some shows, you should DJ our shows” and so I did one show with them just for that first cash payment that I needed. But then they were like, “we want to do more shows!” I said “no, I can't do it” even though they were paying me a lot of money. It was no because it was not what I was trying to be known for. It wasn't what I was trying to do. When you are navigating within yourself and you've come up on something that you know is you, you have to rock with it. You have to. You have to. Most people don't talk about the no. There's a huge part where you have to say no to a lot of things to get what you want. A lot of people talk about the yes part, you know what I mean? But the no part - that's gigantic. It’s about knowing what it is that you're supposed to be doing on your instrument or with your creativity and then executing that.

The power of no is essential. You’ve talked about Michelle and Rob as critical relationships in providing opportunities for you to experiment and hone your unique approach. I know a few talented artists who struggle with social isolation and may not have those connections to call in when they need a lifeline or a chance. Can you speak on the art of maintaining connections? What advice would you give an artist who struggles to cultivate key relationships?

Photograph of Jahi Sundance (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

JAHI: I think the best way that I found to build relationships with the people that you want to have relationships in this business, people who may be famous or maybe successful and you want to align yourself with them. The best way is to never be pushy, always be respectful, and always be persistent. Now there's a difference between persistent and pushy. Pushy energy is energy that people don't like. Persistence is really consistent, not annoying. Those are two different things - being consistent is something that somebody will recognize. Being annoying is something that somebody will never talk to you again for. You have to determine what those nuances are because they are nuanced approaches. For example, instead of calling someone or emailing them or hitting them on social media everyday with your mixtape, try to find out if that person is giving a talk or doing an event. Go and introduce yourself. That kind of approach will get you really far versus like, “I got all the stuff, I got a new mixtape and I'm the man” approach. Like that's one approach but you need money behind you to do that, you know what I mean? If you're going to do that and you got a rich backer, do it. Go for it. But if you're just out here struggling, it's just you. You're in the hustle. You got to be humble and you got to make yourself available for people. You have to be open to those people who you believe in. If you believe in someone, that's who you got to rock with.

Such generous advice. Damn, Jahi - thank you! Pivoting back to the music for a moment. In Sonny’s Blues, James Baldwin writes about how he imagines the relationship between the musician and their instrument to be fraught, “awful” in fact, since he has to fill it with “the breath of his own life” meaning, he has the difficult task of animating the piano or the trumpet with his own aliveness, his own emotion - volatile and messy as it is. I resonate with this curiosity and wonder how the tension produced in music might also express itself in improvisation and in blue notes. Can you speak to where and how you create tension in your music?

JAHI: Well for a lot of instrumentalists, it's about their relationship with practice. Because once you get to a certain point, performance is the easiest part of the entire relationship. At least for me, I think for singers that changes - the performance may not be the easiest part. But for instrumentalists, the performance is the easiest part. If you're the lead tenor player, the lead guitar player, the drummer, and whatever the performance is, the show is the fun part. That's the easiest part. You know what I mean? So the tension in the music is their relationship to practice.

But for DJs, at least for me and for other DJs I know, it's about your relationship to being a jukebox, right? So for me, escaping that as much as possible was the goal of being on stage. And so the fact that I put words into some of these instrumental tunes is what creates some tension sometimes. For example, we were in Brazil and Bolsonaro was the president and he's a Brazilian Trump, for those of you who don't know. But worse, because he's in Brazil and gets away with way more shit, you know? And so before the show, I went out into the street and did like two or three street interviews with people from Brazil in Portuguese. Even though I don't speak Portuguese, I brought the tour lady with me who spoke Portuguese, and I had her help me. And we did some interviews about Bolsonaro. I had people say statements about Bolsonaro into my phone. And then on the show that night, we played at a state house and there was people from the government there in the top.

They were in the balcony seats because we played in like an old opera house type place, like a state place that's owned by the country. And so towards the end of the set, we do Kendrick Lamar, “How Much A Dollar Cost”. And I usually play snippets from police shootings in America on Black people before we go into that song. But it was because we were in Brazil, I played all these Bolsonaro clips of people being like, “Fuck this guy!.” And the entire bottom of the crowd went fucking crazy. They were so happy. They went nuts. And everybody in the top, all the government people in the suits all got up and left. They all got up and left. And the next day they wrote us up in the paper. It was a big controversy and shit. So as far as bringing tension, musically, I feel like maybe the people who have more chordal note responsibility can bring more musical tension. My tension that I bring as a DJ is going to be emotional tension to the format. And that's really what I've been able to tap into and create.

Do you feel like there is like a ripening that happens in the music as you mature as a person? Toni Morrison and Octavia Butler wrote some of their heaviest works later in life, with all of that experience pulsing through the language. Sometimes when we’re younger, we still feel a need to prove something and then as you ripen, hopefully you start to transform and shed that compulsion to justify or outsource your worth. What do you think?

JAHI: Well, there's a couple of paths with that. When you're on a path that's more left, it's a longer path and you have to have a longer patience level. You know what I mean? Like in terms of national notoriety. Everybody on this interview knows who The Roots are but they had to wait a long time to become a nationally known group who never had a hit record. And that's the way that goes. So if you want to do something that's different, that's actually different, genuinely different, it's going to take a long time. Or you're going to have to know somebody and get in and and fight people. If you could do it that way when you're young, do it. Because that's the other way is to know someone and get in and then you just got to fight people. The whole way. If you're going to do something different, you're going to have to fight people the entire way. And that's just the way it is. You know what I mean? Like, it's just what it is. Ask anybody who did it and they'll tell you about all the fights that they had.

So there's the other way where you don't really fight people because I didn't really have to fight people in my career. It just takes a long time because you have to align with people and figure it out and you have to be there when the money is slim. And the money is slim and the money is slim. The money is slim. And hopefully you're doing that in your twenties. You know what I mean? Because the money is slim all through the twenties and then you get to the thirties and you're like, “now I'm supposed to have it?” Nope. It's really your mid-forties where it starts to hit if you're on this kind of racket. This is where the beginning is - your mid-forties of when it starts to hit. If you look at any of the careers of these really famous people who are left, look at look at what happens in their mid-forties, that's when it starts to go crazy. Quincy Jones, even though he had obviously produced Frank Sinatra and all these other people when he was like 17. Like Thriller doesn't happen until his mid-forties. So all these things that don't happen until you're mid-forties, like as far as like if you want to be this kind of like totally left or very different kind of artist, it's not going to pop for you till then. It's just not, you know what I mean? It's just not.

At 35, I find your insight both reassuring and humbling. The money sure is slim still. Mid-forties, here I come! I definitely resonate with the slower path that requires a higher level of patience. I think we’re all working in different time signatures and that’s okay. This is a bit of a cheesy question but since the path isn’t linear and the payoff is often delayed, how do you enjoy the ride? There’s a lot of talk about “self care” these days (taken out of the original revolutionary context) but I am interested in your wellness practices on tour and if you have any perspective on the explosion of wellness as an industry - particularly in LA.

JAHI: I feel like on the road with Rob, we all do a pretty good job of it. We'll stop off in a place and everybody will get massages. We'll go do stuff like that. You got to take care of yourself, especially on the road because you can get sick and it's a lot of traveling. But really for me, on a personal level, it's an out loud gratitude habit that has nothing to do with social media and nothing to do with meditation. My out loud gratitude habit, which is something that I will execute as a stopgap when I'm feeling depressed or something that I've made a habit of that I do at specific times every time and out loud, meaning not to yourself, but to another person expressing how grateful you are for them. This kind of thing has worked better instead of being grateful for the things in my own life. You know, for me this solution is better. Any time I feel myself slipping into a depression or any of that kind of shit, I make a list. And the next day I will call those people on that list and ask them, “Hey, you've got 5 minutes? I want to tell you how grateful I am to have you in my life, the things that you've helped me do, and blah, blah, blah, blah.”

You do those phone calls and then you feel better, you know what I mean? Every time I'm on tour with Rob or Michelle or anybody I tour with or have toured with in the past, they will tell you sometime right before the end of the tour, I pull everybody together, whether it's my band or not, and tell them how grateful I am for them allowing me to be on stage with them. These habits create a circle around me again of people who care about me rather than just people who I work with. And that allows for a different kind of relationship with the music.

And so those are things that I do on a personal level. As far as wellness overall? Wellness overall is a huge business just like any other business in America. When you apply the concept of infinite growth to anything, you have done something that is antithetical to all the laws of the universe, aside from the universe itself. So in a sense, when you apply infinite growth, you are saying you are just as powerful as the whole universe, which you are not.

I’ll be sitting with what you just said for awhile. Thank you for sharing both your personal “out loud” gratitude practice and your sharp critique of the commodification of wellness for profit. I have just one last question for you, which I’m asking everyone. Can music heal?

JAHI: Music definitely heals, there's no question. That's like a fucking fact. People are in a coma and then they put the headphones and then they're like, “Whoa, I'm awake! You played my favorite song? Oh, yes, I'm aware and alive.” You know, all that kind of shit. Music definitely heals. But I think the strongest thing that music does is gives us reference for our lives. Music is like a big appendix, like footnotes, like if you hear a song, then you see the little number next to the song and then you can go to the chapter, you know what I mean? And it just plays for you and it's one of the strongest things that allows us to experience times in our lives when we were happy or times in our lives when we were sad or times in our lives of anything. And all those ways in which we are listening and listening to things as we're going through stuff attaches those things to those experiences. it's just nice. You'll hear a song and it'll remind you of a person, a place or a thing, and you'll just have a whole memory set and then it feels good, you know?

Beautiful answer, Jahi. Thank you! It's been such a pleasure speaking with you. This has been one of my favorite interviews in a minute. I’m looking forward to the next time we talk. Ok, Last last question: what do you want more of?

JAHI: In the world, I would like to have less greed. But in my life, I would like to have more money.

Jahi Sundance has an album out called Love Isn't Enough with Robert Glasper, Meshell Ndegeocello, Chris Dave and more. Look out for his next project coming out in the Fall.

ALEX ISLEY

Photograph of Alex Isley (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

Alex Isley is rooted in a deep sense of family pride. While she’s most known for being the daughter of Ernie Isley of the prolific Isley Brothers, her familial and musical influences extend even further back.

One thing is for certain, soul and musical ability are Alex’s birthright and she has the tone and perfect pitch to prove it. In his autobiography Treat It Gentle, Sidney Bechet describes music as, “a feeling inside of [himself], a kind of memory that wants to sing itself.” I’ve always been curious about this strange dance between musicianship and memory, between technical skill and what Quincy Jones calls, “leaving space for God to walk through the room.”

This notion that music can dictate what it wants to say brings me to a related inquiry about the healing properties of sound. Can music heal?

Against the backdrop of a heritage oak tree, Alex stands poised in a cerulean pleated two-piece set, embodying the elegance and quiet strength of someone at peace and in their purpose.

Photograph of Alex Isley (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

Alex, it’s such an honor to speak with you! In preparing for this interview, I noticed a theme of self-care in both your music and even in the Tiny Desk you put out in 2020. I'm curious to hear more about your wellness practices and how they might buoy your creative practice?

ALEXANDRA: Self-care really began for me even more so once I became a mom. And I think I had always thought about parenthood as so sacrificial and you're just giving up on yourself. And I just thought I was just always going to be just running behind my little one. But I learned ironically, that the most important thing about parenthood is taking care of yourself so that you're in a position to take care of your child, your children, how you should. And so motherhood was the beginning of being even more purposeful towards my me-time and ways I can just pour into myself and better myself.

How has motherhood transformed the way you make music? My sister has two kids and she's a working artist and I remember her reflecting back to me that becoming a mother strengthened her art practice. I'm curious if that resonates at all for you of it’s something different?

ALEXANDRA: Absolutely. Motherhood has made me way more intentional with my time and and how I create. It's made me more patient with myself, like being okay with not being inspired every second of the day. Or sometimes I might feel like I want to create, but nothing's coming to me. And so being patient in that way too. So yeah, motherhood has taught me patience. Having grace, giving myself grace and just being even more intentional.

Speaking of family, every interview I’ve read of yours starts with the interviewer contextualizing you within your family lineage. And while coming from such a heavy legacy as The Isley Brothers is something to be seriously proud of, do you ever crave standing apart from it? Even for just a moment. Can you be grateful for your family legacy while also shining on your own or are you inextricably tied for the better?

ALEXANDRA: That's my foundation. I think, no matter what, there's always that sense of family pride. They are extremely encouraging and supportive of what I do. And that means the world to me to have that. But honestly, I'm influenced by so many other things. I studied jazz in college and so there's a lot of that in my artistry and how I perform. I'm influenced by West Coast hip hop. You know, growing up in LA, I'm also influenced by 90s R&B so there's so much more in the pot. And so I feel like that's helped me elaborate on the lineage while also carving another path for myself because I think I can do both. I I can be proud of where I come from, but also step out and go in another direction.

I love your “yes and” answer, that resonates. I’m always curious about the balance between formal training and more nuanced influences including coming from a musical family and the ways in which the music is inside us from birth. What would you say are the ingredients of being a musician or artist that can't learn in a classroom?

ALEXANDRA: You can't learn the love. And I genuinely love performing. You're born with that or you develop that naturally. But yeah, you can't learn that or be taught that. So, for sure the love for what I do can’t be taught and everything else comes after that and falls into place. Yeah, I just genuinely love to do this.

And since we're at Blue Note, I have to ask what was your relationship to jazz growing up? And how has it evolved overtime?

ALEXANDRA: So my maternal grandfather dabbled in jazz when he was younger. He was a dentist for many years because his parents wanted him to pick a practical job, but he had a passion for jazz drums. He was really the beginning of my jazz education. I learned who Oscar Peterson and Billie Holiday were and I came across Ella and Duke eventually but I didn't really get into jazz until high school, when I heard the vocal jazz group singing "Lush Life." I didn't know what it was, but I was like, ‘whatever this is, I want to sing it!’ And that was the beginning. I sang jazz all through high school and then ended up studying it in college at UCLA. And so, at this point, it's such a part of everything I do, how I perform on stage, how I interpret a song, how I write a song, how I interact with players on stage. It’s impacted everything and it’s such a huge part of my artistry.

Photograph of Alex Isley (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

Can you speak to how you tap into emotions you may or may not be experiencing when you perform? Both you and Bilal possess this tremendous capacity to move me to tears with every vocal performance and I’m awed by the emotion you stir in us, the listener. I’ve always been curious about how you connect and channel the feeling even if it’s not fresh to your direct experience. From what well do you dig from?

ALEXANDRA: I think sometimes it may not be necessarily about connecting to the emotion of what it is I'm singing, but sometimes it's just connecting to the feeling, like how the music itself feels. And a lot of times that's how I feel. Sometimes the music is dictating to me what it wants to say. Most of what I've written has come from personal experience. So most times I can tap into it. But when there are moments where I may not necessarily identify with being heartbroken, for example, it's just the feeling of the music itself that lends help with that.

It’s so powerful that the music itself is communicating through you. I feel that deeply when I see you perform. In the same spirit as this question, do you believe music heals?

ALEXANDRA: Music absolutely heals, it definitely has healing properties. I have seen, even scientifically, it has been proven. So music is absolutely healing. It doesn’t matter the language or the instrument. If it strikes a chord, then that's just the connection - that's the heart connection. And so I think that's something really special because music really has no boundaries to me.

Photograph of Alex Isley (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

How did you and Jack Dine meet? You two have such undeniable chemistry, was that there from the beginning or a slower build? I'm interested in the intimacy created between collaborators.

I met Jack in mid-2019. I wasn't sure what was going to happen when we first met but we created something that then became our song called “Wait”. And so we just really liked to create. Eventually, we just made it a thing where I was coming weekly and then he was like, “let's put out a project!” and I was like “Okay!”. So we put out “Wilton” eventually in November 2019. And then both of us were like we should do an album and just keep going. And so, I don’t know where the endpoint will be. But, you know, he’s stuck with me for life I think, at this point. The chemistry and the trust that we've developed is just very organic and I’m very grateful for that because you don't come across a dynamic like this. I haven't really had something like this.

Jack Dine and Alex Isley

Alex Isley has an album out with Jack Dine called “Marigold” featuring Robert Glasper on “Still Wonder.”She will be touring a city near you this month through September.

AMBER NAVRAN

Photograph of Amber Navran (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

LA based singer, producer, and woodwind player, Amber Navran radiates a warmth and infectious joie de vivre both on-and-off stage. Amber kicked off the festival on Friday with pianist and producer Kiefer, the legendary Chris Dave on drums and Pera Krstajic on bass on the “Blue Note Napa Stage” right at the entrance of the Charles Krug Winery. Playing a mix of familiar hits, unreleased music and even a cover of Mario’s “You Should Let Me Love You” and Beyonce’s “Me, Myself & I,” Amber’s set embodied her range, skill and playful spirit.

AMBER: It was so much fun! I've been such a huge fan of Kiefer for so long and we've had these ideas for a long time but life gets busy and he has this project and he's on the road and I'm on the road with Moonchild. It's really nice to have a reason to get together and finish some stuff. I was a little nervous about performing unreleased songs because I feel like audiences want to hear stuff they know, but a jazz festival is a great place to do it because people are coming a little more open minded, wanting to hear something different from what they know you for. I thought it went well. I had a really good time and we got to play with Chris Dave, which made us really happy. And our bass player was Pera Krstajic and he is so good and just a really joyful person too - always smiling. So it was a really fun set!

Though Amber performed on Friday, she stayed through Sunday to enjoy this history making multi-day festival experience, catch up with friends and connect with other artists.

AMBER: It has felt like a reunion, especially the artist area. It's set up to be such a hang. There's a basketball court, a bunch of couches, amazing food and a lot of spaces where people can get together and catch up. A lot of us haven't seen each other for so long and everyone is just so sweet and wonderful. You're just walking down the path and people are coming up and giving you hugs, you know? It's been the best, best weekend I could ever ask for.

Photograph of Amber Navran with Emily King back stage (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

Jazz musicians share a certain shorthand with comics as both deal in timing, tension and improvisation. It’s no surprise then that Robert Glasper and Dave Chappelle would combine forces to co-host the festival. In both contexts, I’m curious about the relationship between structure and improvisation, between mastering a form only to eventually break it.

AMBER: I learned structures so that I could break them, so that's where I'm coming from when I'm playing. And once I learned that you can break the structure, I had so much fun! But my husband, Patrick Shiroshi, plays free, improvised music and he's really helped expand my ear and my musical sense of how you can come at the music from anywhere. And if you're coming with emotion and passion and intention and, you know, trying to build something or trying to create new sounds on an instrument, there's just so many ways you can approach it.

There’s a longstanding assumption that heartbreak generates the best music but many contemporary r&b and soul artists are pushing back by consciously creating from a space of joy / emotional diversity. Amber embodies a life-affirming energy both in her sound and song choice that stands out.

AMBER: I'm sure this is true for most songwriters or artists but creating is my therapy. I process a lot of what I'm going through through the music. And so of course, you know, as an artist and just a human that includes like a lot of self-doubt and a lot of moments where you're like, “Why do I do this?” And so sometimes being in that place, you can write a song for yourself or the things that your friends say to you or the things that you read or the things that get you through those times. I feel like it's really healing to write from a place where you're feeling down, but then it's also so lovely and wonderful to come to a song to just talk about the joy that you feel.

Photograph of Amber Navran wearing BRWNGRLZ (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

Not every artist is born into a musical family or finds and develops their passion for music early on in life. And while Amber joined the school band at a young age and went on to pursue jazz saxophone, she didn’t start singing until much later in her career. Amber shares hard-earned wisdom about being patient on the long, non-linear journey of honing one’s voice.

AMBER: I feel like I've grown so much in so many ways. When we first started Moonchild, I had just started singing. So I feel like the last ten years have been me really finding my voice and feeling comfortable in my voice and my body - especially in the past few years, especially with ‘Starfruit’. For me personally, I know where my voice sits anywhere that I want to go, which took a long time. I think it takes everyone a long time to get there. But I didn't grow up singing, so I spent a lot of time early on feeling really self-conscious about learning while creating. But looking back, I really feel like at the end of the day, it's about the songs and the lyrics and the feel of the song and the emotion that the song and the track is bringing. I feel like coming from the jazz world, especially playing saxophone, the easiest horn to play, you know, like all saxophone players have moments in their solos where they're ripping because they can and it's really killing and impressive and amazing. But coming as a vocalist with all of that background, I spent a long time feeling self conscious about it. And honestly, our career has taught me that that's not at all what it's about. It's nice when it's there and knowing your instrument is important. But yeah, I feel like now I have more confidence because I know myself better and my instrument better. It’s easy to feel like you have to be amazing at every single thing you do. And now I feel like I just want to come and be myself and make melodies and just be honest in the music and that's the best I can do. And that's okay with me.

Artists are more likely to be asked questions about responsibility than politicians. Surely, this says something about how little politicians are held accountable or maybe it reveals more about who's asking the questions. But perhaps, more importantly, it says something about how powerful artists are and how we look to them for cues on how to respond, reimagine and remember. As Amiri Baraka famously said, “there are people who actually believe that politicians are more powerful than artists, what a bizarre lie.” In truth, it’s critical for each of us to contend with our responsibility and our specific positionality in relation to power - openly and out loud.

AMBER: I definitely think responsibility is the right word for white musicians. I think all white people have a responsibility to combat white supremacy in whatever space they exist in. And I feel very aware of that responsibility being in Black music. I really want to just bring whatever I can to the table respectfully and in a way that feels good and helpful and not in the way. I think it's something that we should all be doing. And I do see a lot of people doing it, which makes me happy. But yes, it's definitely a responsibility that we all have.

Photograph of Amber Navran (2022) by Ashleigh Reddy

Is music a mirror reflecting our reality back to us, a hammer smashing the image reflected in the mirror, a portal teleporting us to new worlds or deeper within ourselves? All or none of the above?

AMBER: Music is just really healing. If I'm feeling like quitting or just like feeling down or like, ‘why do I do this?’ I know that if I go into my closet studio and make a beat, I'll feel better. And sometimes it takes me too long to get in there and do it, you know? Like when you know the answer, that doesn't mean you do it right away, but it just I feel so empowered and I feel like the most like myself in that space. And it feels really playful. It doesn't feel like there's judgment around, you know, I feel just feel really free and playful. And so that's what it is for me. And I'd like to think that that translates to people, you know? I hope it does.

MOONCHILD has an album out called “Starfruit”. Amber is currently working on an album with Jacob Mann and Phil Beaudreau that will hopefully come out next year under the name Cat Pack. She is also working on an album with Kiefer alongside several other exciting collaborations. Stay connected to her on all social platforms.

Smokin Grooves 2022 Recap on Okayplayer

Photo of Syd by Ashleigh Reddy

“It’s been a minute but it’s getting better, right?” Thundercat said it plain and he was right. It's been a hot minute - 855 days to be exact according to Acoustic Soul Queen India Arie. This year’s Smokin Grooves marked many artists' return to the stage since the pandemic hit in March 2020. The air was thick with anticipation on Saturday as artists and music lovers gathered at the Los Angeles State Historic Park for what felt like a much needed family reunion. Folks came fitted and ready to be seen, eager to spark something and get a taste of live music’s medicine.

Photo of Thundercat by Quinn Tucker

With two stages boasting competing lineups, festival attendees took different approaches from some ambitiously weaving between both to others moving n’ grooving comfortably from the grass. The Jupiter Stage featured an eclectic mix of hometown heroes like Blu & Exile to the legendary vibraphonist and genre-defying vocalist, Roy Ayers. And while both stages faced significant sound and production problems throughout the day, Saturday’s special blend of moody skies, trees and soulful selections by way of Soulection’s Joe Kay kept the vibes high. Fans were blessed with classic cuts and new music exclusives from artists like Oakland R&B royalty Goapele to every hip hop head’s favorite electronic band, Little Dragon.

Photo of Bilal by Ashleigh Reddy

As I made my way to the Main Stage after spilling out all my guts to Philly legend Bilal sing an electrifying rendition of “Sometimes”, I spotted none other than OG Dr. Chill, father of Slauson songbird, Jhené Aiko Efuru Chilombo, suited and booted, giving out hugs freely and embodying the spirit of divine love. In that moment, it struck me that these small moments of spontaneous connection and fellowship are what we’ve all been missing. Live music has always created a necessary context for people to come together and unite through its spellbinding power. And even in the tedious moments of long bathroom and food lines, I observed people make new friends (even if it was bonding over shared complaints), reunite with old ones and find the silver lining in the inevitable messy swirl of festival life. In his flawless performance, R&B powerhouse Miguel reflected back, “attention is the ultimate currency these days” and he’s right. It’s an increasingly rare experience to have that many people’s attention coordinated in one direction. If his high wattage smile was any indication, it felt really good to receive.

Photo of Miguel by Ashleigh Reddy

As “one spliff a day will keep the evil away” boomed from the speakers, Inglewood’s own SiR suddenly stopped singing to request a medic for concert goers who had presumably passed out in GA. In the wake of last year’s Houston AstroWorld tragedy, it was reassuring to see artists apply lessons in real time, prioritizing the safety of everyone over entertainment. Later in the night, Jhené followed suit, checking in with fans multiple times and eventually leading all of us through a collective breath and ending her set with a tender plea for 8 hours of sleep. We’ve come a long way from hip hop’s old adage “sleep is the cousin of death” and personally, I’m here for it. That said, the original architect of N.Y. State of Mind, Queens’ own, Nas lit up the main stage with nostalgic hits I grew up on from “Made You Look” to “One Mic”. In the middle of his performance, nature conspired with him as the sky opened up and rain began to pour down on us. At that moment, sleep was the furthest thing from my mind.

Photo of SiR by Ashleigh Reddy

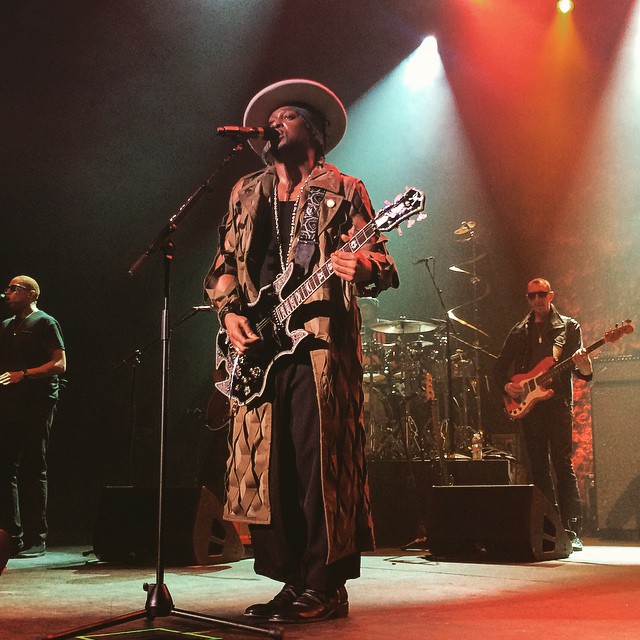

The king of breath control and master of ceremony, Black Thought proved why he is one of the greatest emcees of all time. The Legendary Roots Crew showed out with a massive display of talent from "Captain" Kirk Douglas shredding on guitar, Questlove killin’ on drums and Damon Bryson rocking out on his signature giant tuba. Everyone around me was mesmerized by Tariq’s impeccable cadence and the perfectly composed and executed transitions between songs.

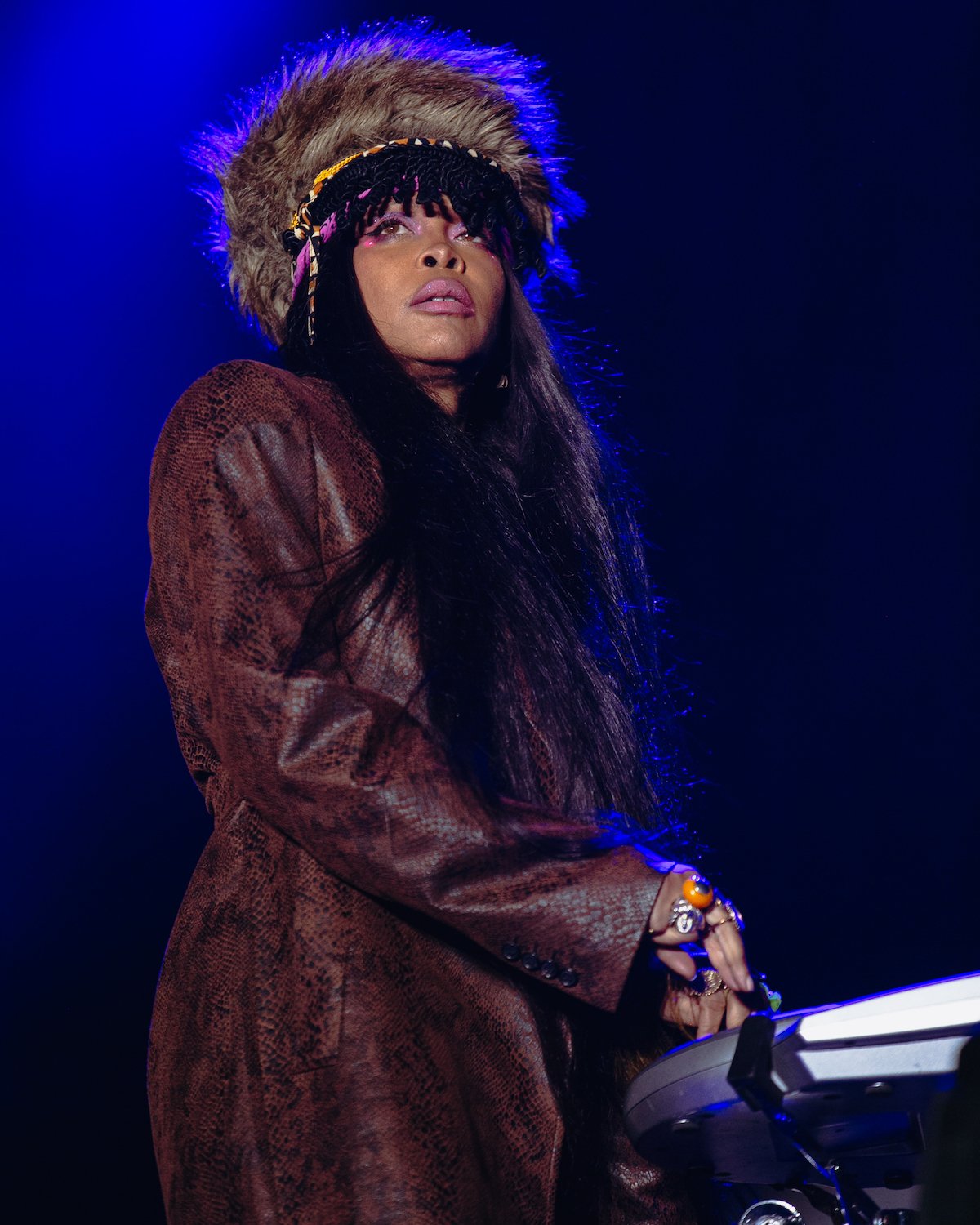

Photo of Erykah Badu by Ashleigh Reddy